Note: All charts below were created with Matplotlib and Seaborn.

My most recent project at Metis entailed using court sentencing data to predict whether a defendant pled guilty, or was found guilty by a jury at trial. By total coincidence, the dataset I used on guilty sentences from the county in which I live, Cook County, IL. While I thought predicting the conviction type of a particular case would provide insight into the power of plea bargaining, I had no idea that it was also closely tied to a long-standing controversy within the US justice system.

Upon speaking with a close friend about my project, I was pointed in the direction toward a Chicago Tribune article on “jury tariffs,” a concept which refers to the price defendants pay in increased sentences when they take their case to trial instead of pleading guilty. We expect the same penalty for the same crimes, but jury tariffs suggests that this is often not the case. According to one anonymous Cook County Judge quoted in the Chicago Tribune article, “Not having a jury trial can save a lot of time and effort. Pragmatically speaking, it’s necessary and it’s justified to give a guy a tougher sentence if he takes more time and burdens the system.” (Tybor, Joseph R. & Eissman, Mark. “JUDGES PENALIZE THE GUILTY FOR EXERCISING RIGHT TO JURY TRIAL.” Chicago Tribune, 13 October 1985’) While some may see logic in this judge’s efforts to keep the justice system from becoming backlogged with too many cases, the reality (as stated in the Chicago Tribune article) is that “the Illinois Supreme Court has ruled on several occasions that the accused cannot be punished for electing to have his case decided by a jury.” (Tybor & Eissman)

With this court ruling in mind, if we were to compare sentencing lengths between defendants in Cook County who committed similar crimes, we should not see major differences between the defendants who pled guilty and defendants who went to trial. If defendants who go to trial are receiving longer sentences than defendants who plea guilty, then jury tariffs might be influencing a given case.

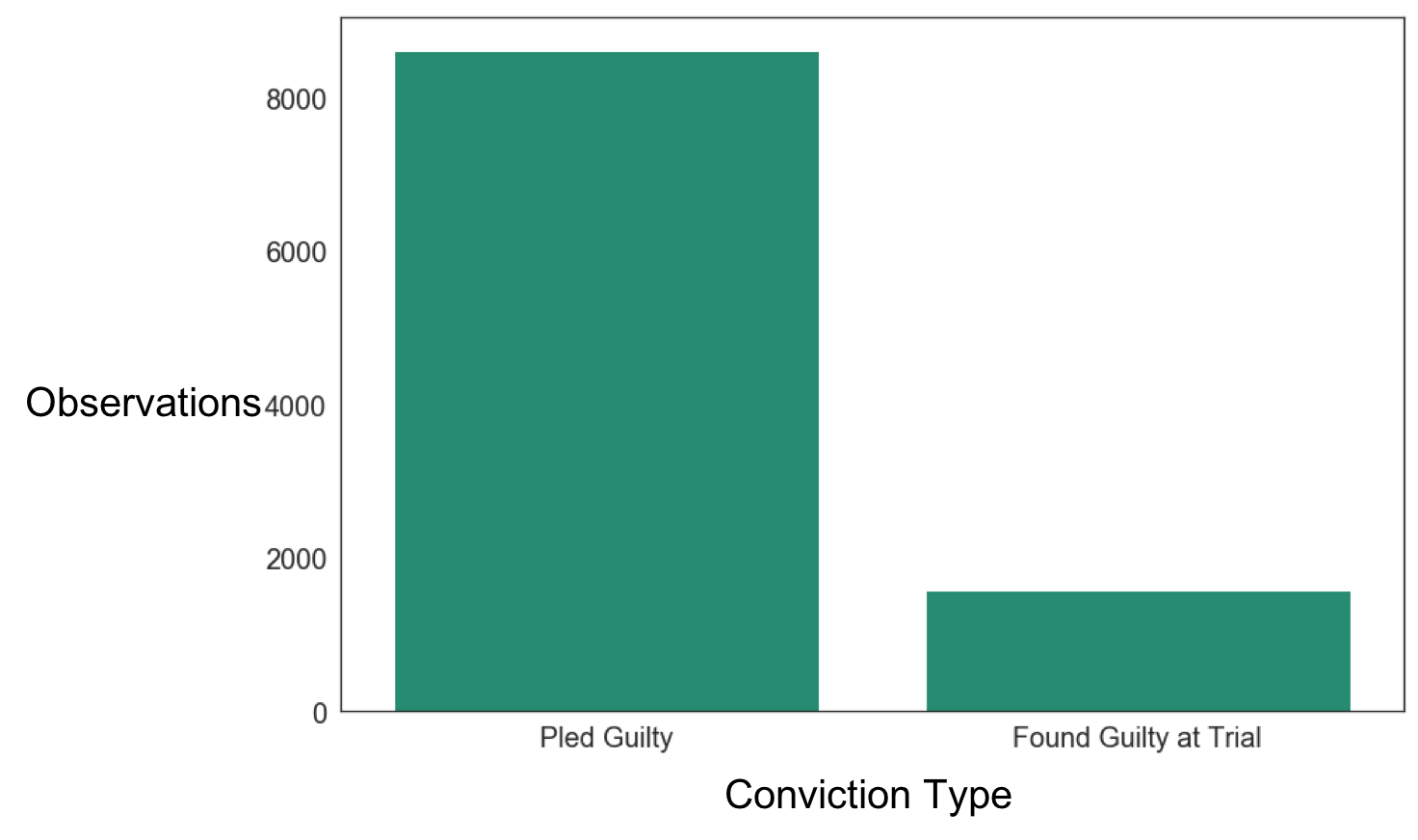

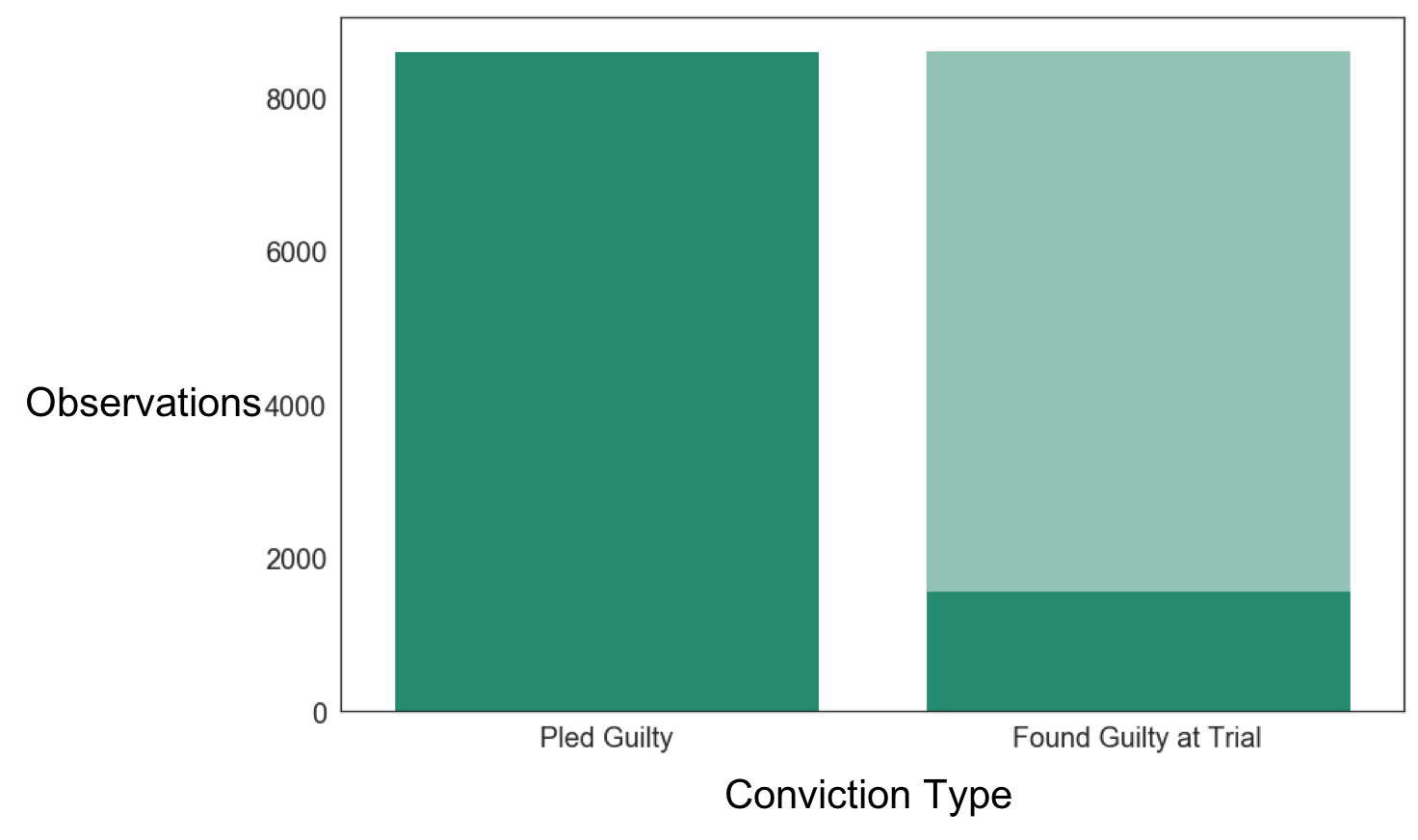

To test this effect, I built a random forest classifier on 10,000 guilty murder cases from Cook County, IL. I decided to look at murder cases exclusively so I could compare defendants who committed similar crimes. As 85% of these defendants pled guilty and avoided trial, the raw data yielded an imbalanced data source.

To address this data imbalance, the sample of defendants who went to trial was artificially enhanced using upsampling so that the model could train on an equal distribution of binary classes.

The random forest model was 87% accurate, so overall it did a good job of distinguishing between these two classes. But what were the differences between these two classes?

On average, defendants who pled guilty received an 8 year sentence, while defendants who went to trial received almost double that with an 15 year sentence. Though on the surface this trend supports my initial hypothesis that defendants who go to trial are receiving longer sentences, another statistic suggests that this is largely being caused by self-selection.

Defendants who pled guilty had 1 charge against them on average, while defendants who went to trial and were later found guilty on average had 2.5 charges against them. Though defendants who go to trial do receive almost double the sentencing length as defendants who avoid trial with a guilty plea, they are also more likely to choose to go to trial when they have been charged with more crimes. This bias provides evidence against the existence of jury tariffs in Cook County because defendants are not being penalized for deciding to going to trial. Additionally, number of charges was the best predictor in my model so this variable seems to be strongly correlated with a defendants decision of how to approach their plea.